Sublime Heights

A Brief Essay on Cássio Vasconcellos Panoramic Photo Images

“When Matisse still believed it was possible to teach art to his pupils, he once told them that one of the richest lessons they could learn was through air travel, so that they would see the world differently, fostering a new sensitivity by adopting a different point of view. Cássio Vasconcellos is a photographer that not only has been wise enough to benefit from that advice, but has also turned it into a way of living. His present work is increasingly fed on the aerial photographs the artist has taken during his helicopter flights throughout the world.

The series of panoramic photo images Cássio started in 1993, when he edited some older photos he had shot, has represented an important stage in the artist’s poetic formation. The word panorama, a term that is made up of Greek elements and means a vision of the whole, was coined in 1792 by the English painter, Robert Barker, during the London showing of his pictures of Edinburgh. In 1793, still in London, he made a fortune when he opened his panorama to the public. As early as 1787, Barker had patented his invention, which “allowed for seeing nature as if the watcher was actually there.” In order to reach such an effect, a strong mastering of perspective projection techniques is indeed required.

Panorama must be understood in the context of the great technical transformations occurred in Europe between the 10th and the 19th centuries, a period that saw the development of optical devices (camera obscura, lenses, stereoscope, microscope, photographic camera and cinema) that widened the human visual horizon dramatically, from microscopic scale to the macroscopic one. Since them, the paradigm according to which human perception is based on one (and only one) perspective, defined by some cyclopic eye, has been put into question. The eye has come to be understood as a moving mechanism with several focal points.

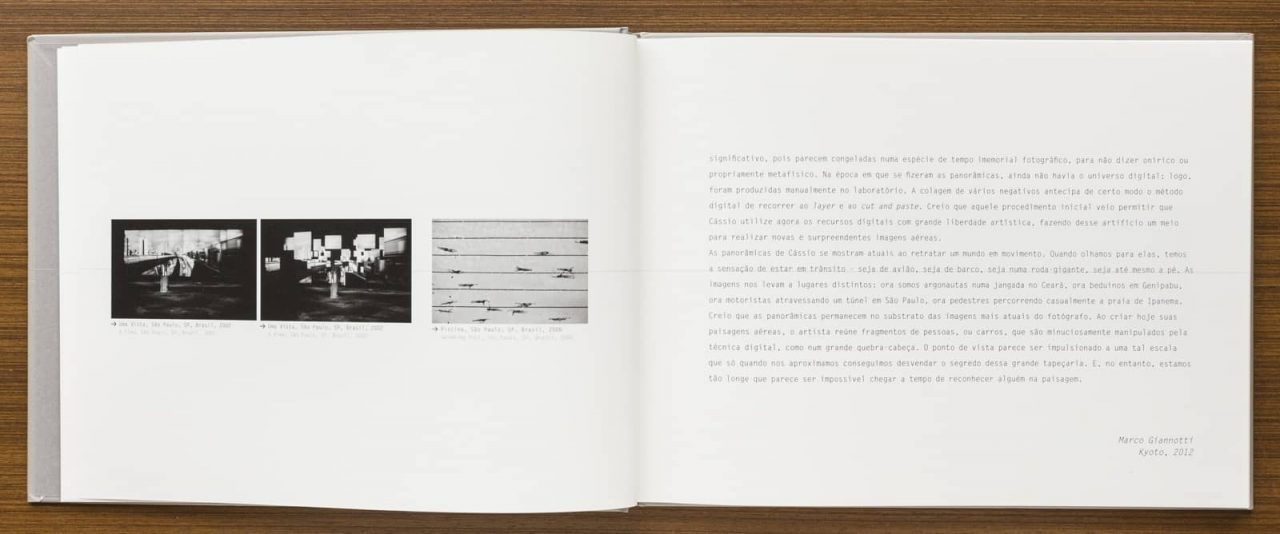

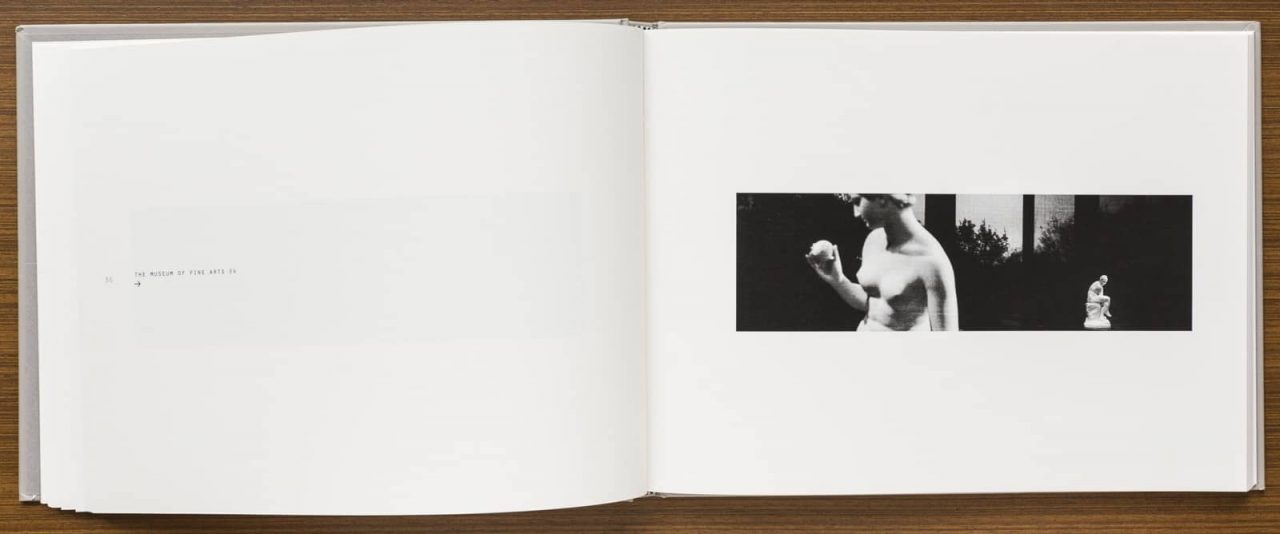

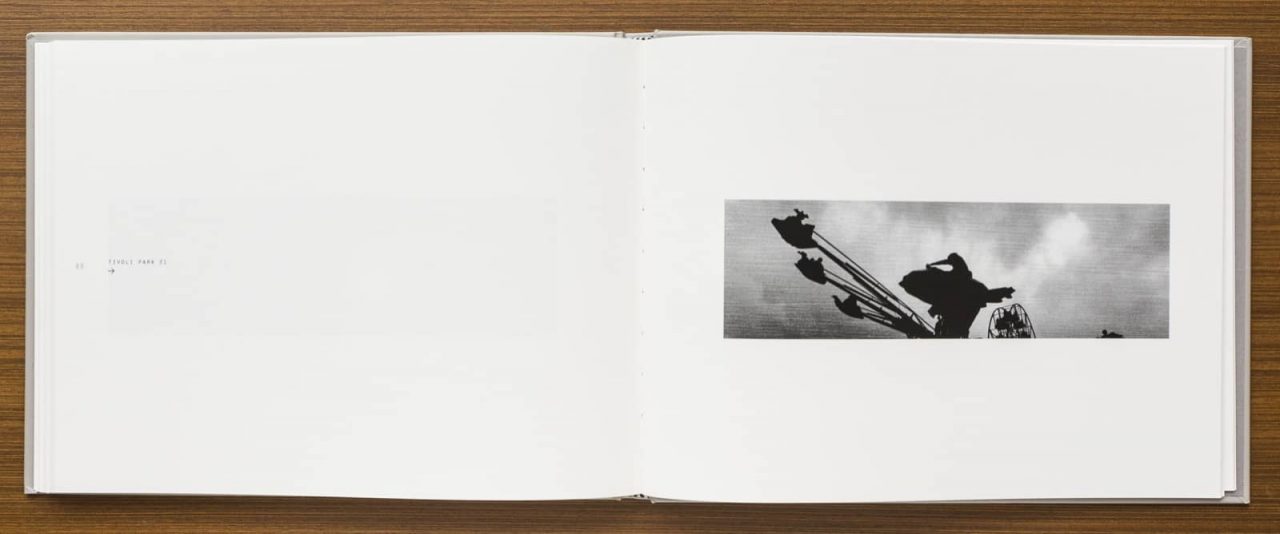

In significant moments of his career, Cássio made large-scale installations, which consisted in several photographs that offered a single, unified image when watchers viewed them from a certain vantage point. Unlike Barker’s, Cássio’s panoramic images are modern, immediate because they show a moving world. When we look at them, we feel panoramas (which could be as large as 250 square meters, or 2.700 square feet), Cássio’s panoramic photo images are small-format ones: their scale sho great compositional quality, where element are set in such way as to evoke an always wider space. When figure appear, they are always dissolved into a grand landscape. Thanks to the juxtaposing of thin layers of clear adhesive tape and negatives, the topographic, tactile aspect is set against what lies far away – a visual play that is crucial in rendering the panoramic effect, which brings watchers closer to the image and, at the same time, distances them from it.

The photography of mountains cut with incisions, which suggest a rudimentary form of writing, makes quite explicit the search for the image’s tactile dimension. That photos are in black and white is equally meaningful, for they look frozen in some immemorial (if not oneiric or even properly metaphysical) photographic time. At the time the panoramic images were made, there was no digital universe yet: therefore, they were made manually at the photo lab. In a way, the collage of several negatives anticipated digital methods like processing layers and making use of cut-and-paste. I believe that initial procedure eventually enabled Cássio to apply digital resource with the great artistic freedom he enjoys and uses nowadays, turning them into means to produce new, surprising aerial views.

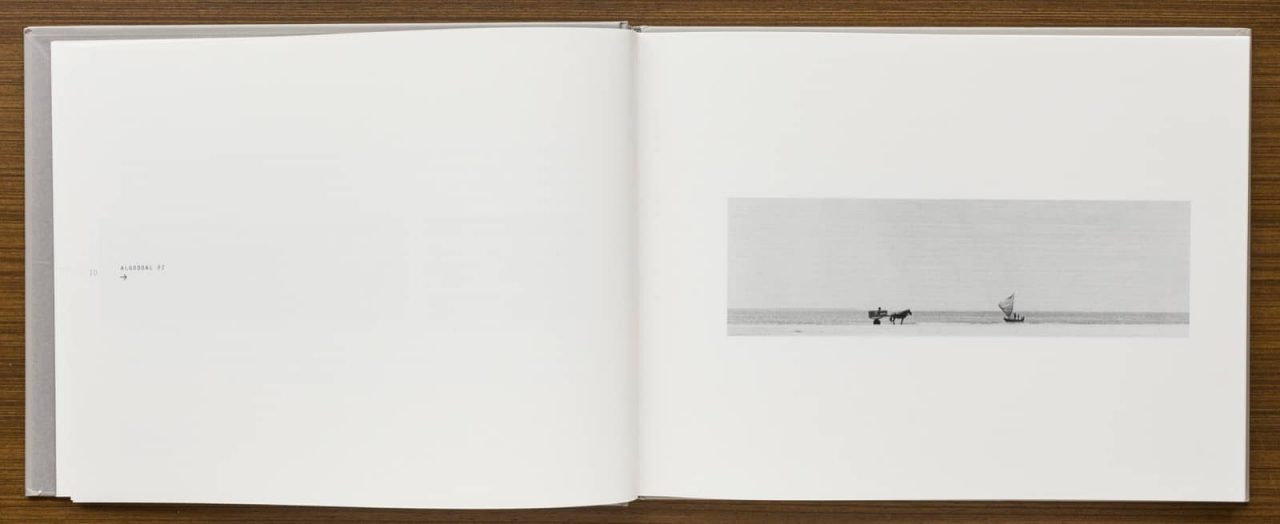

Cássio’s panoramic images are modern, immediate because they show a moving world. When we look at them, we feel as if we were moving too – by aircraft, by boat, in a Ferris wheel, even on foot. The images takes to different places: we may be Argonauts on a fishing raft off Ceará. Bedouins on the sand dunes of Genipabu, drivers going through a tunnel in São Paulo City or walkers passing casually by Ipanema Beach.

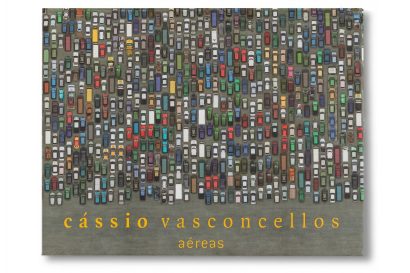

I believe these panoramas remain subjacent to the photographer’s most recent images. When the artista creates his present aerial landscapes, he puts together fragment of people, or cars, which are minutely handled through digital technique, as if in a big jigsaw puzzle. The vantage point seem s so withdrawn that only when we get closer we are able to unveil the secret of this grand tapestry. But we are so far away that is seems impossible to arrive in time to recognize someone in the landscape.”

Marco Giannotti

Kyoto, 2012

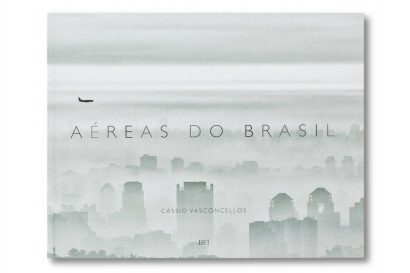

Panorâmicas

Graphic Design: Eliane Stephan

Text: Marco Giannotti

São Paulo: Editora DBA, 2012. 28,5 x 21,8 cm; 108 pp.

ISBN: 978-85-7234-453-4